Every serious disc golfer from novice to professional wants to get better at the game. While we all know that practice is the answer, figuring out how to practice disc golf effectively has long been a frustrating process.

Whereas sports like basketball and baseball have had over a century of professionals developing tried-and-true training methods as well as over 80 years of top athletes on TV for anyone to see and copy, disc golf as we know it is around just 60 years old. Video coverage of largely self-taught top players hasn't been widely available for much more than a decade, and disc golf coaches are close to non-existent. For most of disc golf's history, the best those seeking to improve could hope for was something simply clicking during field work or getting a few hot tips from a local talent.

However, recent developments in the world of disc golf training options and technology are changing this status quo. With some big shifts just getting underway, we thought it'd be a great time to look at what disc golf practice has looked like throughout the years and the most exciting modern developments.

Disc Golf Practice's Humble Beginnings

Disc golf as we know it today got its start in the late 1960s and early '70s as heavy marketing by Wham-O of their Frisbees led to a huge surge in interest in the plastic flying saucers. But early Frisbee enthusiasts – most of whom saw golf as just one of many interesting disc skills – had no blueprint of kinesthetics or form.

It didn't take too long for people to try to impart knowledge in print, though. Examples include 1972's The Official Frisbee Handbook by Goldy Norton of Wham-O (which only touched lightly on disc golf), the magazine Frisbee World that started up in 1976 with Dan Roddick – inventor of the two-meter rule – at the helm, and 1977's Frisbee by the Masters by Charles Tips that came complete with groovy illustrations of shirtless men demonstrating technique.

While some people assuredly picked up useful pointers from texts, the best ways to get better at the time were to A) figure out what worked through practical experience and B) befriend an expert and learn all you could.

A Shift to Video Cassette

With the widespread adoption of VHS in the eighties, companies started producing videos to make disc skills appeal to a larger audience.

Eventual hall-of-fame disc golfer "Crazy" John Brooks released the video above in the early '80s while touring with Bud Light as part of a freestyle disc collective. Much of the video clip deals with freestyle, but it does touch on aspects of disc golf that are still used today. Brooks mentions how to use rollers effectively and how firmly to hold a disc. But the differences in the Frisbees of yore and today's disc golf discs are clear from tips like his "parakeet test," where he says you should hold a Frisbee like you would a bird – hard enough to keep it from flying away but not firmly enough to kill it. The power grips used by modern disc golf pros would mean bye, bye birdie.

In the '90s, VHS tapes of the Pro Disc Golf World Championships became available, allowing more amateurs than ever before to see and attempt to copy the forms of the most successful players in the world. However, the VHS quality was poor and the emphasis was on the outcome of throws rather than the players throwing. You can again see John Brooks in the video clip of the 1993 World Championships below along with a young Scott Stokely, who jumped back into the touring game a few years ago at over 50 years old.

There were also videos released in this era that specifically focused on teaching basic disc golf skills, such as Learn to Play Disc Golf with now-renowned course designer John Houck in 1995. If you give it a watch, you'll notice the techniques described are fairly similar to what we see today.

Though these videos existed, they weren't always easy to find or get your hands on. Remember that it was an age where having a home computer with internet access was far from a given and search engines were nowhere near as advanced or widely used. To find these videos you needed to be lucky or in-the-know.

Just like when the sport started, the best way to learn tended to be finding good players and paying close attention. Phillip-Tyler Belt, a skilled player who recorded a round in 2022 that was the highest-rated at any competition sanctioned by the Professional Disc Golf Association that year and is tied for the sixth highest-rated of all time, told us about his experience of learning to play in the pre-YouTube era as a young kid.

"I had a really supportive mom who wanted me to learn how to play disc golf because I was passionate about it," Belt said. "She would take me to doubles all the time at the local course and pay the $15 to play. I would mainly lose the money but every now and then I would draw a good partner and he would carry me. My local area was rich in good disc golf players so I got to watch a lot of them play in doubles, and that’s where I learned the most. I would watch and analyze how everyone would throw and use the pieces of peoples throws that I found beneficial to my throw. I’d look at angle of pull back, rotation of hips, and other things like that."

YouTube & the Digital Era

The launch of YouTube in 2005 caused a paradigm shift. Almost immediately, users were uploading tutorials, form videos, and – mostly – footage of goofing around on the disc golf course. Among the first 10 videos uploaded with "disc golf" in the title was a series of nine tutorials by Berlin Open champion Mikael Birkelund, who went on to design the second-highest rated disc golf course in Denmark. He discussed forehand rollers, loft putts, turbo putts, and even grenades. The trend never stopped, and YouTube quickly became the destination to learn how to improve at disc golf.

While it's impossible to list all the channels that came and went during the early years of YouTube, there are some notable names. Much of the initial disc golf content was made by companies that had a clear interest in getting their brands in front of as many disc golfers' eyes as possible, like Innova and Discraft. With the rise of social media and the idea of having a personal brand, professionals started to create their own channels. For example, three-time U.S. Disc Golf Championship winner Will Schusterick started uploading tips videos in 2010.

Not long after, a trend of amateurs who made content with drills and general disc golf information while also documenting their own journeys to improvement started. One of the most recognizable faces of this movement is Danny Lindahl, and you can check out one of his earliest form tips videos below (just FYI, his production value improved greatly over the years):

Today, there are dozens of YouTube channels with thousands of subscribers that focus primarily on disc golf practice. One of the current major players in this space is Overthrow Disc Golf. We've spoken with Josh White from Overthrow before and discussed the coaching side of things but wanted to get his take on how how YouTube fits into the world of disc golf practice.

White was a disc golfer by hobby but a tennis instructor by trade before starting the Overthrow channel with his friend, fellow tennis instructor, and disc golf buddy Mikey O'Brien. The two saw a lot of good information about disc golf form on YouTube but a serious lack of solid videography. O'Brien had videography experience, and the pair's time as tennis instructors made them adept at analyzing athletic movements and helping others improve at them. They believed that by combining those skills they could make disc golf training videos that would look more professional than anything else available and provide clear, focused instruction.

"We saw that from a video standpoint, quality-wise, there was some value we could add," White said. "We wanted to condense the instruction and increase quality. I wanted to bring simplicity and clarity to instruction."

While you'll see some disc golf training content filled with cryptic jargon and complicated diagrams of swing paths, White wanted to avoid getting too far into the weeds. His main goal is to help players quickly identify flawed areas of their technique and give them effective tools to fix them.

"Nowadays there's too much information," said White. "And this is coming from someone who's giving the information. You need one thing to focus on, and then you need to get after it deliberately and iron that sucker out. You gotta ask yourself inside the information age that we're in, 'What's really important for this?' Deliberate practice is worth, almost, more than knowledge."

Deliberate practice is a style of practice in which you push past the routines that gained you initial success and work above your current skill level. You must continually seek out weaknesses and push beyond them, otherwise you'll plateau. Overthrow attempts to assist in this style of practice in their videos as well as via Zoom coaching classes and in-person clinics.

As surprising as it might seem, he also emphasizes the importance of in-person training where available.

"YouTube's not optimal, and I'm the first one to say it," White said. "It's just not the way that people should learn physical instruction most of the time."

Because practice consists of repeatedly building upon the correct physical motions, White sees a combination of high-quality online instruction and in-person practice as the eventual end goal.

"I think we're actually trying to find a way to go back to how people learned before, which is mostly important," said White. "The supply and demand we have right now — such a low supply of coaches. I teach people in Japan, Finland, Brazil — all over the world because there are just not that many coaches in Finland or in Brazil."

Along with YouTube tutorials, there are filmed disc golf training materials featuring professional disc golfers from undertakings like Pulsea and Power Disc Golf Academies. However, the need to pay to access content – between $8-$20 a month for Pulsea and $75 a year for Power – means their reach is far smaller than free content's.

TechDisc

The newest and most advanced practice tool out there is TechDisc, a piece of hardware from Michael Sizemore and John Carrino that analyzes your real throws and presents what it discovers in an easy-to-understand format. The data it records can help you find your strengths and weaknesses as well as see when a change in technique is hurting or helping your throw.

A Kansas City native, Sizemore played disc golf in high school but got heavily involved in the sport while attending Notre Dame. After graduating and moving to several different cities over the years, he settled back down in Kansas City, started a family, and worked as an electrical engineer with Bushnell.

After hacking a golf rangefinder to make it display distance in feet instead of yards, Sizemore used it on the disc golf course to great success. He convinced Bushnell to bring the rangefinder to disc golf in 2020 and this led to an exploration of using actual metric data in disc golf – an idea he immediately chased further.

"I've always wanted to make a sensor on a disc," Sizemore said. "Just being an electrical engineer, designing circuit boards with sensors and wireless technology is just something that I love doing. So trying to put that on a disc has been something I've been wanting to do for 10 years."

After asking around the Disc Golf Pro Tour for any fellow enthusiasts at the intersection of data and disc golf, he connected with John Carrino, a software engineer from Silicon Valley. As a side project during the pandemic, Carrino had been placing sensors onto discs to monitor his spin and speed. The two quickly partnered up and began creating a more professional circuit board that could be mass-produced and widely sold.

"Probably one of the most fun puzzles to solve was minimizing the components, getting them in the right spots," Sizemore said. "Balancing the battery life versus the weight. I think one of the bigger challenges was just creating disc golf metrics — like deciding what are the important data points and how they should be displayed — because that didn't really exist before."

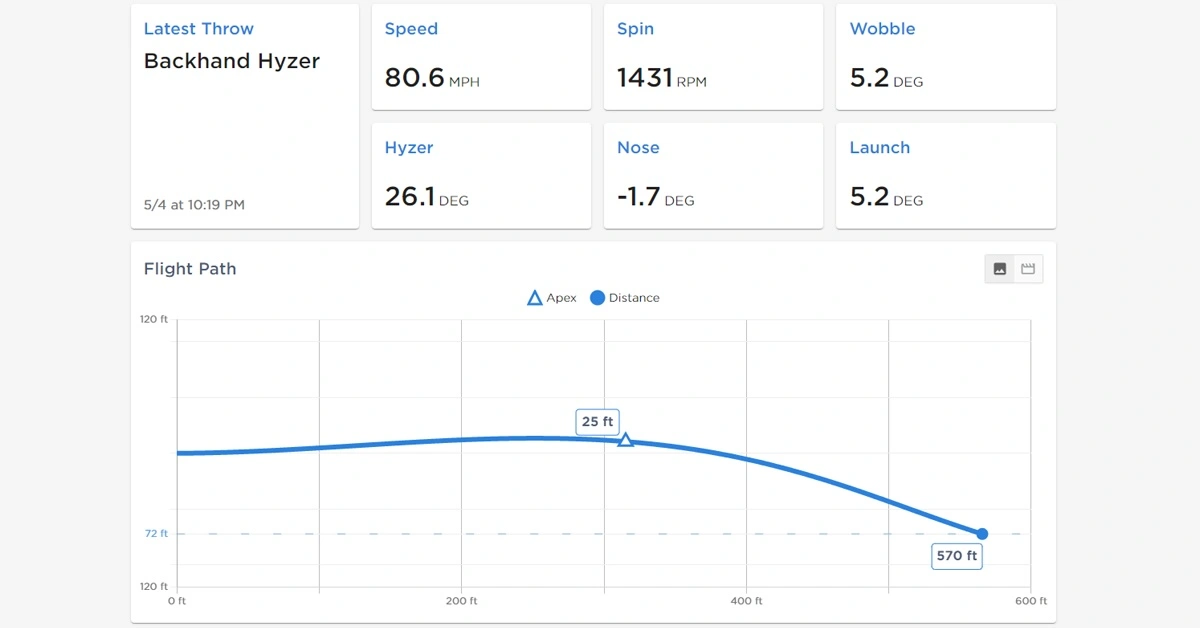

The two landed on a two-by-three grid that displays speed, spin, wobble, hyzer angle, nose angle, and launch angle. These statistics are gathered by high-grade, high-range accelerometers and gyroscopes within the first 20 milliseconds of the throw, sent back to a phone or computer via Bluetooth, and stored in the cloud within three seconds. Each TechDisc user has their own dashboard where they can see all their past throws as well as their averages and trends. While Sizemore had some coding experience, Carrino's background in software came in handy.

"All that magic was really done by my partner, John Carrino," said Sizemore. "That's something of a specialty of his, and I'd say that's one of the more difficult challenges. I think that's really where some of the magic lies, is the way that TechDisc can make meaningful sense out of that motion."

TechDisc can map out a simulated flight path for the thrown disc in the same amount of time it tracks all other data, which means players can get real throw feedback by throwing into a net. That eliminates the need to find a huge, empty outdoor practice space as well as time-consuming disc retrieval. Sizemore and Carrino have tested out entirely simulated versions of holes at famous courses – most recently, a famous island hole at Champions Landing (formerly Emporia Country Club) that hosts the Dynamic Discs Open (DDO). This leaves the door open for future applications where, much like in regular golf, a disc golfer could practice an entire course in their garage with a TechDisc, a projector screen, and the simulator.

"It's an actual physics simulation based on the available research papers that are out there," Sizemore said. "It's not quite perfect, but the improvements we're trying to make to it are pretty minimal. And it is definitely more true to real life than most people's understanding of their own distance."

As for that DDO data, it was stored online and can be perused by anyone interested in the statistics of professionals. Along with DDO, TechDisc gathered data at several other events if you're looking to compare yourself against the metrics of specific pros.

While Sizemore says TechDisc isn't trying to be a coach, he does see a future where the huge amount of data they've gathered can be used to provide a player their percentile in spin, speed, and other statistics among all disc golfers, giving players an idea of where they can improve. It's this type of data-driven practice that can allow for immediate visual results.

"All the guys around here, we throw the TechDisc quite a bit," Sizemore said. "Almost everybody has added at least five miles an hour to their throw, which is like 50 feet [15 meters]."

The puck is permanently affixed to the TechDisc and is available in putter, midrange, fairway, or distance driver, along with Discraft ESP or Innova Star plastic.

Peripherals like the TechDisc are showing how technology can assist in practice. Overthrow's Josh White says about a third of his students utilize a TechDisc in their coaching sessions.

The Future of Disc Golf Practice

Peripherals like the TechDisc are showing how technology can assist in practice. Overthrow's Josh White says about a third of his students utilize a TechDisc in their coaching sessions.

"It's insane what I can do with a student with TechDisc," said White. "Not because I'm amazing but because to have that data is amazing. I can see numbers and have a pretty good guess of what the issue is. It's expedited problem solving. We can get really focused on just the data that we need. If it's nose angle, well now we have something that's telling us right away. It's giving you that feedback loop so you can make adjustments immediately."

It's easy to imagine the future of disc golf practice as the training montage from Rocky IV, machines calibrating every aspect and training to peak performance. And while we're not quite there, things like the TechDisc are proving it's closer than you think.